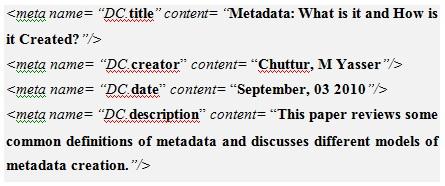

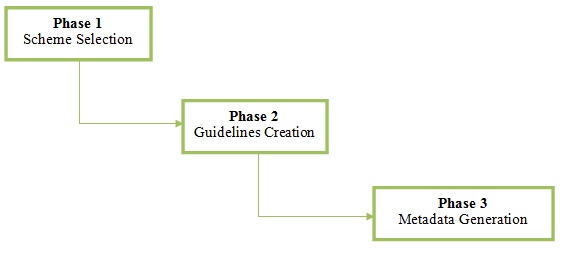

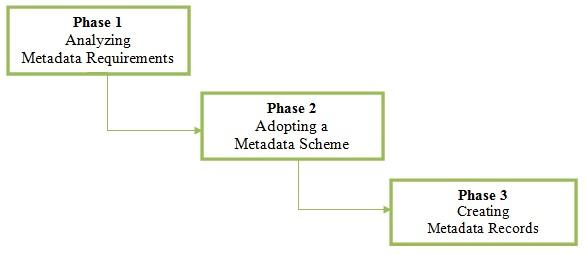

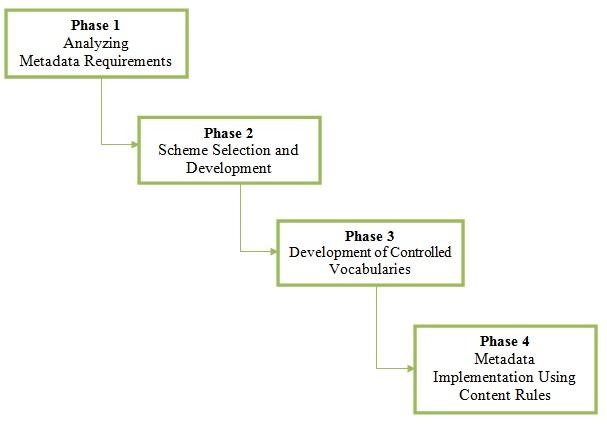

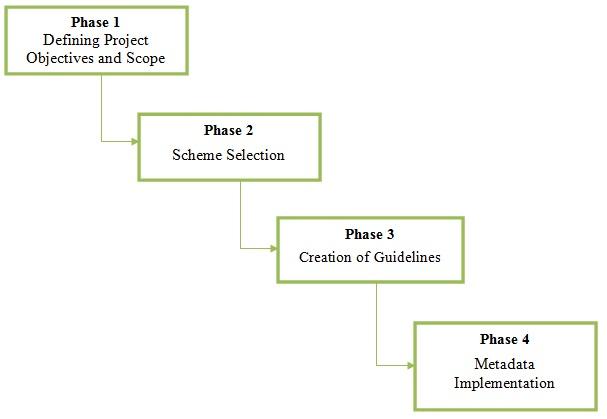

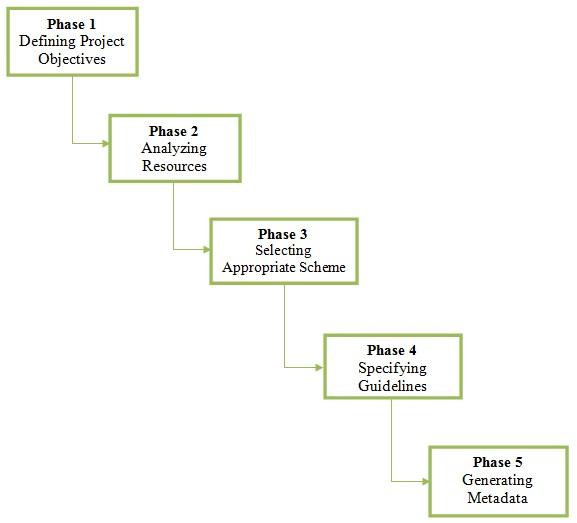

Defining and creating metadata for digital resourcesAbstractWith the unprecedented growth of digital resources, it is anticipated that metadata will become increasingly more important for supporting resource discovery in digital libraries. But the co-existence of multiple and sometimes conflicting definitions of metadata can easily create confusion as to what qualifies as metadata. Similarly, the few models that have been proposed to help practitioners create metadata have a tendency to overlook the sequence that important tasks should occur. This paper reviews the definitions of metadata and clarifies the use of the term within the library community. It also discusses different metadata creation models and problems identified in these models that indicate the need for further research in that area. This paper concludes by suggesting a five-phase approach that takes into account the limitations of other models proposed so far. What is Metadata?Metadata, in its simplest form, is frequently defined as "data about data". The term metadata is itself a fusion of the words meta and data. Meta is a term of Greek origin, meaning after, beyond, or along with (Meta, n.d.), while data is the plural of the Latin word datum, meaning something given or a fact (Datum, n.d.). Thus, the term metadata can be interpreted as referring to something that is associated with a fact or data. In the library environment, definitions of metadata focus on the representation of information resources, where an information resource refers to any digital or non-digital material carrying information, whether textual or non-textual, that can be made explicit. Examples of information resources include books, web pages, video recordings, images, and cartographic materials. Definitions of metadata provided by information professionals often specify both the type of resources for which metadata is used and the purpose(s) it serves, such that, over time, what constitutes metadata has grown in scope to suit the needs of multiple groups. Metadata Definitions within the Library CommunityIn general, definitions of metadata within the library community can be grouped in two broad categories. In the first category, metadata is identified solely with the values used to represent an information resource. Haynes (2004) defines metadata as "data that describes the content, format or attributes of a data record or information resource" (p. 8). His definition assumes that the purpose of metadata is simply to describe information resources and that the "metadata" is the actual value used for the description. Similarly, the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI) defines metadata as "data associated with either an information system or an information object for purposes of description, administration, legal requirements, technical functionality, use and usage, and preservation" (Woodley, Clement, & Winn, 2005). In this case, DCMI considers metadata to be the value(s) associated with a resource, but this definition also specifies a set of purposes for which metadata can be used. The definitions proposed by Haynes (2004) and DCMI focus on the values associated with a resource without specification of what those values actually represent. According to these definitions, the moment a piece of text is associated with a resource such as a book, that piece of text becomes metadata even though it could be anything from a date or title to a comment, review, abstract or an extract from the resource itself. Without knowing the relationship that exists between a value and the resource, little use can be made of the value. For example, without specification of the relationship between the phrase "Thomas Jefferson" and the information resource it represents, it is not possible to determine whether it indicates the author, the title or the subject content of the resource. Obviously, simply identifying metadata as the value(s) describing a resource is not useful. In the second category of definitions, metadata is conceptualized as data that specifies the relationship between a value and the information resource it describes. Arguing that metadata is more than a set of randomly accumulated values, both Gill (2008) and Caplan (2003) define metadata as the structured description of information resources. Many definitions extend this understanding of metadata to include the purposes for which it is used. Thus, the Association for Library Collections and Technical Services (ALCTS) Task Force on Metadata defines metadata as "structured, encoded data that describe characteristics of information-bearing entities to aid in the identification, discovery, assessment, and management of the described entities" (TF, 2000). Taylor (2004), further defines metadata as "structured information that describes the attributes of information packages for the purposes of identification, discovery, and sometimes management" (p. 139), while the National Information Standards Organization (NISO) defines metadata as "structured information that describes, explains, locates, or otherwise makes it easier to retrieve, use, or manage an information resource" (NISO, 2004, p. 1). In contrast to the simplistic definitions of Haynes (2004) and DCMI, definitions that fall into this second category treat metadata as structured data values. Taylor (2004) explains that "structured data" means that the values associated with a resource are recorded according to an external metadata scheme that identifies a set of metadata elements and specifies their semantics, content rules, and syntax. Such a scheme establishes the meaning (semantics) of metadata elements that can be used to represent properties or characteristics of an information resource and provides content rules that serve as the guidelines for selecting values for each element. A scheme also specifies a syntax that establishes how element-value pairs are to be constructed. Understanding metadata as structured data requires that each value used to represent a resource must be paired with, or constrained by, an element that makes explicit the relationship between the value and the resource it describes. Definitions of metadata frequently specify the purposes for which metadata is to be used. However, as Gilliland (2008) explains, metadata can be utilized in a wide range of activities. To define metadata based on purpose creates confusion as to what can be considered metadata. Specifying the purpose(s) of metadata is problematic because each purpose identified in a definition becomes a necessary condition that must be present in order for something to qualify as metadata. Different individuals and institutions may use metadata for different functions, and defining metadata in virtue of the purpose(s) it performs is both unstable and potentially contradictory. Definitions of metadata frequently specify the purposes for which metadata is to be used. However, as Gilliland (2008) explains, metadata can be utilized in a wide range of activities. To define metadata based on purpose creates confusion as to what can be considered metadata. Specifying the purpose(s) of metadata is problematic because each purpose identified in a definition becomes a necessary condition that must be present in order for something to qualify as metadata. Different individuals and institutions may use metadata for different functions, and defining metadata in virtue of the purpose(s) it performs is both unstable and potentially contradictory. A more useful definition of metadata would make explicit the role of metadata in establishing the relationship between a value and a resource without enumerating specific purpose(s) to be served. Thus, metadata is data that represents certain properties of an information resource according to the semantic structure provided by an externally defined scheme. This definition differs from previous definitions in two important ways. First, it does not state the purpose(s) served by metadata and thus does not restrict metadata to any particular application. Second, it makes explicit the idea that metadata, to be metadata, must conform to the specifications of a scheme that establishes the relationship between a value and the resource it represents. Just as importantly, this definition clarifies the distinction between metadata and a mere collection of values that describe an information resource. The popular interpretation of metadata as data about data — or data about an information resource — is, in fact, the definition of a metadata record. A metadata record consists of one or more element-value pairs, or metadata statements, that are used to describe the properties of an information resource. It should be noted that, while all metadata schemes necessarily specify a set of elements and their semantics, some schemes do not prescribe content rules or specify a particular syntax. In such a case, metadata creators are free to establish their own rules and to apply any syntax they find appropriate when creating a metadata record for a resource (Caplan, 2003). An Example of MetadataFigure 1 provides an example of a metadata record that uses the Dublin Core (DC) scheme to describe certain properties of this paper. The metadata statements are the element-value pairs, represented in bold face. These statements were created according to the minimal content rules provided by DC and have been encoded using the XHTML syntax, represented in italics in Figure 1. Because metadata represents the properties of a resource, it can be used effectively in a wide variety of applications, from the simple description of resources for human evaluation to complex information sharing over networked environments. For instance, using the metadata example shown in Figure 1, a person can determine the intellectual content of this paper without having to access the actual resource. Using the XHTML syntax, a system can identify the semantics of each element-value pair as specified by the DC scheme, allowing information about the resource to be matched to user queries for resource discovery. How is Metadata Created?Currier, Barton, O'Beirne and Ryan (2004) have observed that the process of creating metadata records for representing information resources is not clearly understood. There is no standard methodology that prescribes how metadata should be created, and different authors frequently describe the process very differently, making it difficult for practitioners to know which process to follow. It is generally accepted that metadata is not created in one step but is the result of multiple phases, with each phase comprised of one or more tasks. However, descriptions of the metadata creation process generally vary by the number of phases and the sequencing of tasks, resulting in different models of the metadata creation process. Three-Phase Models: Foulonneau and Riley (2008) describe the process of creating metadata for an information resource as consisting of three phases: choosing a metadata scheme; creating usage guidelines; and generating actual metadata records for resources. Foulonneau and Riley (2008) explain that because the choice of a metadata scheme affects the purposes for which metadata can be used, selection of a scheme is the first step in metadata creation. But they also acknowledge that project objectives have a profound effect on the choice of a metadata scheme and that it is essential to identify the properties of information resources that are of concern before actually selecting the metadata scheme. Thus, their emphasis of scheme selection as the first phase is both ambiguous and contradictory. Foulonneau and Riley (2008) seem to disregard the fact that a metadata scheme simply specifies a set of elements that can be used for describing resources: Using a scheme as the starting point for metadata creation would require expending time and effort assigning values to elements without knowing if the resulting metadata would achieve the project objectives or meet the needs of users. That being said, it is more appropriate to consider that identification of project objectives and user needs should precede decisions on metadata scheme selection and not the other way round. However, Foulonneau and Riley (2008) fall short of giving this aspect of the creation process an emphasis commensurate with its influence on scheme selection. The second phase of metadata creation described by Foulonneau and Riley (2008) involves the development of metadata guidelines. They argue that many metadata schemes have incomplete or ambiguous guidelines that need clarification to ensure that metadata can fulfill its intended purpose. According to Foulonneau and Riley (2008), guidelines should contain: information about project goals and the purpose(s) of the guidelines, identify the kind of resources to be described, distinguish between metadata that is to be generated automatically and metadata that needs to be recorded manually, re-state the definitions of elements to be used, provide a cardinality rule for each element, specify the granularity of description desired, indicate any controlled vocabularies, and establish rules for selecting and recording the values for each element. By highlighting the importance of creating guidelines, Foulonneau and Riley (2008) raise an interesting point regarding one of the major difficulties faced by metadata creators when using available schemes. As mentioned by Crystal and Greenberg (2005) and Park (2006), problems in the DC semantics, for instance, often contribute to incorrect application of elements resulting in metadata records that poorly represent resources. Creating guidelines therefore is indeed an important step in the metadata creation process. However, a closer examination of the contents of the guidelines as suggested by Foulonneau and Riley (2008) show that their model leaves the practitioner confused and unclear regarding decisions on project goal and resource selection. In practice, a scheme consists of a fixed set of elements whose semantics, cardinality, and granularity of representation are predefined. For example, DC can generally describe a wide variety of resources, but it is incapable of describing every type of resource or every property of a resource that might be relevant for a given purpose or specific collection. Even if an institution intends to modify a selected scheme by further constraining the semantics of elements (i.e., limiting cardinality or narrowing an element's semantic reference), any such decisions are limited by the scheme itself and may not necessarily be useful for the project at hand or the resources involved. Rather, it would be more effective to consider determining the project objectives, the needs of users and the resources to describe along with the granularity of representation required prior to making any decision on the most appropriate scheme to use. Only then should guidelines be created. Foulonneau and Riley (2008) further explain that the third phase —creation of the actual metadata record— will depend on knowledge and expertise of the different individuals who actually create the metadata records. These individuals will vary in terms of knowledge of the resources and of the rules that guide the selection and representation of property values. Foulonneau and Riley (2008) also state that metadata can be created either by encoding element-value pairs in XML using an appropriate editor or by using a special purpose application, which can provide a template containing fields for the individual to fill in or create the metadata automatically using an algorithm. Regardless of the method used, the final output is metadata. The three phases of metadata creation described by Foulonneau and Riley (2008) are represented in Figure 2. Foulonneau and Riley (2008) identify important tasks that are carried out in each phase of the metadata creation process, but the steps they describe are often overlapping and ambiguous. This illustrates Currier et al.'s (2004) argument that the process of metadata creation is not well understood. Foulonneau and Riley (2008) have a tendency to overlook the causal relationships that exist between decisions: By putting the cart before the horse — by selecting a scheme before first specifying the purpose, user needs and properties of the resource — Foulonneau and Riley (2008) lack sufficient criteria for the choice of the most appropriate scheme, rendering their model confusing and difficult to apply in a practical setting. Other major drawbacks of this model are that, since less emphasis is placed on project objectives, user needs, and resource selection, there is no basis for evaluating project success, user needs may not be met, and metadata creators may find themselves working with schemes that cannot describe resources properly. Ma (2006) also describes metadata creation in three phases (see Figure 3): Analyzing metadata requirements, adopting a metadata scheme, and creating the metadata records. The first of Ma's phases takes into account the goals and objectives of the project, the nature of the collection to be described, the level of granularity required, and the needs of users. The second phase focuses on the need to select elements (and thus an appropriate scheme) that will best satisfy the requirements identified in the first phase. In the final phase, metadata records are created automatically or by human analysis. However, Ma (2006) recognizes that the individuals involved in metadata creation may have different levels of expertise, and he classifies them into two groups according to their level of training: Professional metadata creators are those with extensive training in metadata creation who are able to work with complex schemes, while technical metadata creators are those who have less training and are expected to generate relatively simple metadata. Recognizing that schemes sometimes lack sufficient rules and guidelines, leading to variation in the values of elements, Ma (2006) suggests that best practice policies, including the use of content rules and controlled vocabularies, should be articulated. In contrast to Foulonneau and Riley (2008), Ma (2006) considers identification of project objectives to be one of the primary tasks in metadata creation. Only after identifying objectives and the resources to be described can a choice be made regarding an appropriate scheme. However, by grouping various tasks in a single phase, Ma (2006) fails to make explicit the order in which these tasks should occur. For instance, his description suggests that identification of project objectives and the selection of information resources should take place in the same phase, but these tasks cannot occur in parallel since decisions made in one area will affect other decisions. This should be made explicit by separating tasks into different phases. For example, only after determining project objectives and user needs and analyzing the information resources can one determine the properties of resources that must be represented. Similarly, decisions on guidelines, content rules, and controlled vocabularies should be made prior to the actual creation of metadata records. A more considered description of the metadata creation process would make explicit the order in which various tasks are to occur. Four-Phase Models: Haynes (2004) attempts to address the problem of task ordering by expanding the process of metadata creation to include four phases: analyzing metadata requirements, selecting a scheme, determining controlled vocabularies, and encoding element-value pairs according to established content rules (see Figure 4). He contends that decisions about the use of controlled vocabularies should precede decisions as to which values to assign to elements. Unfortunately, Haynes (2004), too, clusters several tasks that cannot occur in parallel. Apart from the introduction of a phase for consideration of controlled vocabularies, the model proposed by Haynes (2004) is very similar to that of Ma (2006) and his model suffers from the same issues discussed for the model proposed by Ma. The model proposed by Thornely (1999) is also a four-phase approach to metadata creation: defining the objectives and scope of metadata deployment, selecting a scheme to meet project objectives, developing guidelines to provide for consistent implementation of metadata, and creating actual metadata records. In support of her requirement that project objectives must be defined, Thornley (1999) argues that an organization must provide a justification for representing only certain properties of resources; and that specifying the scope of the project will identify the resources that will form the collection as well as the expected environment in which the metadata is to be employed. The last three phases described by Thornley (1999) are similar to those of Haynes (2004). However, Thornley (1999) states explicitly that the development of guidelines should precede the creation of metadata records as shown in Figure 5. As a result, Thornley (1999) places strong emphasis on the need for agreeing on appropriate content rules and vocabularies prior to actual implementation of metadata records. This is particularly important since, as noted by Zeng, Lee and Hayes (2009), some of the major concerns faced by metadata creators often relate to decisions regarding the use of controlled vocabularies and elements to include in metadata records. Thornley's (1999) model, however, assumes that decisions regarding project objectives and resource selection can be taken at the same time. By lumping together both processes as one phase, the question remains in deciding whether to start with specifying project objectives or selecting and analyzing resources first. Clearly these two processes, although very closely related, cannot be carried out at the same time. While resources in collections may trigger decisions for metadata initiatives, it is only after having clearly specified project objectives that resources can be selected and analyzed. If metadata projects were to start with resource analysis, there would be no basis on which to decide which resources to create metadata for and which properties of the resource should be represented. A better approach to model metadata creation activities therefore should make clear the distinction between these two phases. Despite variation in the way metadata creation is modeled, it is important to note that each phase in the process is dependent on the previous phase(s), and any decision made in one phase will influence decisions in subsequent phases, and thus affect the metadata record itself. Zeng et al. (2009) clearly make this point by arguing that "Metadata decisions may be made at different stages of a digital library project, and intelligent decisions are integral to successful implementation of the project" (p. 174). Therefore a useful model for metadata creation should make explicit the different phases in the process as well as the kinds of decisions that need to be made in each phase. Such a model will most likely be very useful for project managers who can plan accordingly and perform task distribution effectively to ensure the successful implementation of metadata projects. Moreover, responses collected by Ma (2007) on metadata creation practices in research libraries showed that the process is usually distributed and decentralized among different sections within libraries. Such a model, therefore, may also benefit workers who are involved in metadata projects as they can be made aware of their position in the process and the impact they may have on subsequent phases. Metadata Creation as a Five-Phase Process: It follows from the above discussions that a more appropriate model for creating metadata should consist of five phases. Since metadata is always created for a well-defined purpose, any initiative should begin with a clear understanding of the purpose(s) for which the metadata is to be used. It is also important to identify potential needs of users and the organization, which will contribute to clearly defining project objectives in the first phase. Thus, a project requiring the creation of metadata records must begin by addressing the primary question: "Why is metadata needed?" as part of the first phase. In the second phase, the important question to ask is "What is the metadata to be used for?" This will guide the selection of properties to be represented in the metadata records as an essential part of the second phase. Answers to these two questions contribute to decisions in the third phase which consist in selecting the most appropriate scheme — a scheme that contains elements suitable for describing necessary resource properties. Selection of the scheme will provide direction for the development of guidelines to assist metadata creators in the fourth phase. These guidelines should establish explicit content rules, identify controlled vocabularies, and define how elements are to be used to meet project objectives. Finally, in the fifth phase, since metadata can be created either manually or automatically, decisions must be made as to how best to create metadata in order to meet project objectives. As shown in Figure 6, these five distinct phases make explicit the decisions that need to be taken for the successful implementation of any metadata initiative. At the same time, they illustrate the effect that each phase has on subsequent phases. The proposed five-phase model is an improved model compared to the three- and four-phase models in three important ways. Firstly, the model makes explicit the sequence in which tasks should normally occur. In contrast to previous models which lump together different tasks that cannot be run simultaneously within the same phase, emphasis is placed on the causal effects that exist between different phases and the need to distinguish between tasks that should occur in sequence. Secondly, the proposed model lists all the major tasks required for successful implementation of metadata records. Previous models sometimes would overlook the importance of one or more tasks either by lumping them together in one phase or simply by not listing them at all. Foulonneau and Riley (2008), for example, did not make explicit any tasks for specifying project objectives and user needs. Thirdly, the five-phase model emphasizes the complexity involved in metadata creation. As pointed out by Crystal and Greenberg (2005), metadata creation is a complex process, yet, little attention has been given to the actual process (Barton, Currier and Hey, 2003). By having more phases and clearly defined tasks, which further involve additional sub-tasks, the five-phase model makes explicit the complexity involved in the process compared to other models which cover fewer phases. In consequence, modeling the metadata creation process as consisting of five phases seems to provide a more practical and effective solution to guide the successful implementation of metadata records. Concluding RemarksThe importance of metadata cannot be overstated. With respect to information discovery, metadata is a crucial element for effective retrieval. In the absence of full text indexing, using metadata is the only way a system can search for and provide access to various kinds of digital information resources. Image and video collections, in particular, frequently lack textual information making their discovery highly dependent on metadata. Defining metadata helps in identifying metadata but previous definitions of metadata have been either too limited or too general. Metadata is also not created in one step, but is the result of decisions made in multiple phases. Different models proposed so far have overlooked the ordering of important tasks in these phases and it can be argued that the process of creating metadata is not well understood. The five-phase metadata creation model proposed in this paper not only identifies decisions that need to be made when creating metadata but also makes explicit the sequence in which tasks should normally take place. Further research is required to test the model and identify any unforeseen problems. ReferencesBarton, J., Currier, S., & Hey, J. M. (2003). Building quality assurance into metadata creation: an analysis based on the learning objects and e-prints communities of practice. In Proceedings of the 2003 International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications: Supporting Communities of Discourse and Practice—Metadata Research & Applications, Seattle, Washington, September 28-October 02, 2003. Caplan, P. (2003). Metadata fundamentals for all librarians. Chicago, IL: American Library Association. Crystal, A. & Greenberg, J. (2005). Usability of metadata creation application for resource authors. Library and Information Science Research, 27(2), 177-189. Currier, S., Barton, J., O'Beirne, R., & Ryan, B. (2004). Quality assurance for digital learning object repositories: issues for the metadata creation process. ALT-J Research in Learning Technologies, 12(1), 1-20. Datum. (n.d.). In Merriam-Webster's online dictionary. Retrieved December 26, 2010, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/datum Foulonneau, M. & Riley, J. (2008). Metadata for digital resources. Oxford: Chandos Publishing. Gill, T. (2008). Metadata and the web. In M. Baca (Ed), Introduction to Metadata [Online ed. Version 3.0] Retrieved December 26, 2010, from http://getty.edu/research/publications/electronic_publications/intrometadata/metadata.html Gilliland, A. J. (2008). Setting the stage. In M. Baca (Ed), Introduction to Metadata [Online ed. Version 3.0] Retrieved December 26, 2010, from http://getty.edu/research/publications/electronic_publications/intrometadata/setting.html Haynes, D. (2004). Metadata for information management and retrieval. London: Facet Publishing. Ma, J. (2006). Managing metadata for digital projects. Library, Collections, Acquisitions, & Technical Services, 30(1-2), 3-17. Ma, J. (2007). Metadata. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries. Meta. (n.d.). Dictionary.com Unabridged. Retrieved December 26, 2010, from Dictionary.com website from http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/meta NISO. (2004). Understanding metadata. Bethesda, Maryland: NISO Press. Retrieved April 10, 2010 from http://www.niso.org/standards/resources/UnderstandingMetadata.pdf Park, J. (2006). Semantic interoperability and metadata quality: An analysis of metadata item records of digital image collection. Knowledge Organization, 33(1), 20-34. Taylor, A. (2004). The organization of information (2nd ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited. TF. (2000). Task force on metadata: Final report. Retrieved May 20, 2010, from http://www.libraries.psu.edu/tas/jca/ccda/tf-meta6.html Thornley, J. (1999). The how of metadata: Metadata creation and standards. In Proceedings of the 13th National Cataloguing Conference, Brisbane Queensland, October 13-15, 1999. Woodley, M. S., Clement, G. & Winn, P. (2005). DCMI Glossary. Retrieved May 15, 2010, from http://dublincore.org/documents/usageguide/glossary.shtml#M Zeng M. L., Lee, J., & Hayes A. F. (2009) Metadata decisions for digital libraries: A survey report. Journal of Library Metadata, 9, 173-193. AcknowledgementsThe author wishes to thank Dr. Elin Jacob for reviewing an earlier version of this paper. Special thanks also go to the editor of the Library Student Journal for his valuable suggestions in reviewing earlier submission of the paper. Author's BioM Yasser Chuttur is a doctoral candidate at the School of Library and Information Science, Indiana University Bloomington, where he also teaches a course in metadata to future librarians and information professionals. |

Contents |

Copyright, 2011 Library Student Journal | Contact

international · peer reviewed · open access

international · peer reviewed · open access