Questions by Keystroke: An Analysis of Chat Transcripts at Albert S. Cook LibraryAbstractTo remain relevant in the increasingly digital 21st century, librarians need to engage with users at point of need. Chat reference provides such an opportunity. To understand the types of questions users ask via chat reference, transcripts logged over the course of an entire semester were analyzed and categorized by type. The frequency of the different types of questions was calculated to determine if the number and proportion of question types changed over the course of the semester. This data gives librarians a better understanding of chat reference users and allows librarians to anticipate user needs. Introduction & ObjectiveAs the world becomes increasing digital, it remains necessary for librarians to engage with users at point of need. Chat reference provides such an opportunity. As a relatively new mode of reference practice, there are many questions about how library users take advantage of this service. Because chat transcripts can be easily logged, they provide not only a reliable record of what occurs during reference transactions, but also an excellent opportunity for library professionals to reflect upon (and research) how chat reference is utilized. For the purpose of this study, the fall 2010 semester of chat reference transcripts from Towson University's Albert S. Cook Library was analyzed to ascertain the types of questions being asked as well as the frequency of different question types. This data would provide an understanding of how chat reference is utilized in order to anticipate students' needs. BackgroundTowson University (TU) is the "second-largest public university in Maryland [and] is a member of the University System of Maryland, the nation's 12th largest public university system" (Towson University, 2011). Located in Towson, MD, just north of Baltimore, a major metropolitan hub, it is largely a commuter campus. TU enrolls a total of 21,840 students: 17,529 undergraduates and 4,3ll graduate students (Towson University, Office of Institutional Research, 2011). Of the 111 degree programs Towson offers, 63 are undergraduate, 44 are Masters, and 4 are doctoral (Towson University, 2011). Towson is one of the largest producers of nurses and teachers in the state of Maryland. Cook Library's chat reference service, known as Ask a Librarian, can be accessed using the purple Ask a Librarian button that may be found in the top menu bar of Cook Library's homepage. This button will bring up a pop-up with a LibraryH3lp chat widget. Chat reference can be accessed in other ways as well. For each discipline, a subject liaison librarian has created a subject gateway, a web page filled with sources selected for each discipline. On the right-hand side of each of these pages, there is a LibraryH3lp chat widget. Additionally, students may access chat reference via Blackboard, an electronic course management system, and simply by adding the library's chat reference username to his or her chat buddy list. Posted hours for chat reference are Monday - Thursday 9 a.m. - 9 p.m. and Friday 9 a.m. - 5 p.m. In practice, however, questions are answered any time a librarian is available and signed into Pidgin, the universal chat client that Cook Library uses. A more accurate depiction of chat reference hours would be 7:30 a.m. - 10 p.m. Monday - Thursday, 7:30 a.m. - 8 p.m. Friday, 12 p.m. - 8 p.m. Saturday, and 2 p.m. - 10 p.m. Sunday. Chats are managed using an open source chat application called LibraryH3lp. This application allows chat to be queued. This means that as soon as one librarian answers a chat question, s/he is the only person that can instant message (IM) the user. Librarians can transfer questions if it becomes apparent that the user's question would be better answered by another librarian or subject liaison. Additionally, LibraryH3lp records chat transcripts and can run some statistical reports concerning the number and frequency of IMs. Literature ReviewMuch of the literature surrounding chat reference deals with analysis of transcripts for both question type and quality of transactions. Chat reference transactions are easy to record, providing accurate documentation of how reference questions are handled. This allows assessment of reference transactions in a way that has not been possible previously with traditional face-to-face reference. When reference questions are coded, they are analyzed and divided into categories to determine patterns. Most often questions are coded to determine what kinds of questions are being asked, but questions may also be coded to determine who is asking questions, when questions are asked, or any other facet the researcher can imagine. The articles reviewed include coding of questions by question-type as only one aspect or approach to evaluation of a chat reference service (Arnold & Kaske, 2005; Breitbach, Mallard, and Sage, 2009; Broughton, 2003; Foley, 2002; Kibbee, Ward, and Ma, 2002; Lupien, & Rourke, 2007, Maximiek, Rushton, and Brown, 2010; Rourke & Lupien, 2010; Sears, 2001; Wan et al., 2009). This allows for a well-rounded analysis of the many facets that comprise chat reference. Other facets of study include demographics (Arnold & Kaske, 2005; Broughton, 2003; Foley, 2001; Maximiek, Rushton, and Brown, 2010; Sears, 2001); qualitative analysis of transactions for both behavioral performance and accuracy (Arnold & Kaske, 2005; Kibbee, Ward, and Ma, 2002; Maximiek, Rushton, and Brown, 2010; Sears, 2001); surveys of chat reference users (Broughton, 2003; Foley, 2001; Kibbee, Ward, and Ma, 2002; Rourke & Lupien, 2010); surveys of chat reference providers (Breitbach, Mallard, and Sage, 2009); patterns in patron language and behavior (Rourke & Lupien, 2010; Lupien & Rourke, 2007); length of transactions (Breitbach, Mallard, and Sage, 2009); patterns in usage during specific days and times of day (Broughton, 2003; Foley, 2001; Kibbee, Ward, and Ma, 2002; Maximiek, Rushton, and Brown, 2010); comparisons of different chat reference systems (Rourke & Lupien, 2010); patterns in usage of co-browsing software (Wan et al., 2009); and feasibility of chat reference as a long term service (Breitbach, Mallard, and Sage, 2009; Foley, 2001; Kibbee, Ward, and Ma, 2002). Analysis of chat reference is in its early stages within the field of library science because chat reference itself is a relatively new library service. There is not yet consensus within the field concerning the best way to analyze this data. Because most of the studies consider question type as only one facet of analysis, broad categories are used to code question types. Lupien and Rourke, however, used both broad categories, as well as subcategories. This allowed for greater specificity in determining question types, which allows for greater specificity of knowledge of user needs. This greater specificity means that greater care needs to be taken when examining the transactions: While the focus was on the questions rather than on the answers, it was often necessary to examine the entire transcript to determine what the student was asking. Classification of reference questions is a difficult task, as the question asked is not necessarily the question that needs to be answered. Furthermore, many sessions involved more than one question. (Lupien & Rourke, 2007, p. 70) The burden of work required to properly identify and categorize question types may be why many studies stick to broader categories. It is easier and less time-consuming to differentiate among broad questions types. Lupien and Rourke limited each transaction to be categorized as only one type of question, despite the fact that multiple questions may be asked and answered during the course of each transaction. Like the use of broad categories, this is another approach to limit the burden of work for question categorization (2007). Another study of chat reference transactions completed by Arnold and Kaske warrants a closer look because it was conducted at the University of Maryland, a consortial member in the University System of Maryland and Affiliated Institutions along with Towson University (2005). The University of Maryland is a much larger school in comparison with Towson, but it is the school most comparable to Towson in the state of Maryland both in size and scope. Arnold and Kaske focused on how question-types differed among user-types. For each of these groups, Arnold and Kaske subsequently analyzed the accuracy of responses (2005). This study was notable because it was the only studied examined that tabulated number of questions "deferred, referred, or lost because of technical problems" (Arnold and Kaske, 2005, p. 182). For the purposes of the Towson study, while referrals were counted, it would have been preferable to incorporate more categories like this in the analysis of data. The Towson study did not count questions that were not answered because a staff member never responded or questions that were illegitimate, such as spam. This strategy was taken for two reasons. First, this study focuses on questions that have been asked. Since the question asked cannot be determined without a reference interview, questions that were left unanswered were not analyzed. Second, spam was excluded because these IMs provided questions that were not genuine reference questions. The exclusion of these transactions was a way to limit the burden of analyzing chat reference data. One of the earliest studies of chat reference services was completed by Foley. Categorization of questions was one of many aspects addressed in her study, but transcripts were not generated in an effort to protect patron privacy. Additional measures used by Foley include a patron survey, librarian reports of transactions, and usage statistics (2001). Earlier studies, like the one conducted by Foley, seem more concerned with establishing an overall picture of, creating benchmarks for, and evaluating the usability of chat reference. Later studies delved deeper into the nitty-gritty details of chat reference because a general concept and benchmark had already been established by studies like the one completed by Foley. Researchers dug deeper into chat reference after the viability of the service had been established. Hypothesis & MethodologyMy research began with my curiosity about the types of questions asked via the Ask a Librarian Service and how TU's librarians answered those questions. As a new staff member to TU and a student of the Library Science field, I created a goal of reading all of the chat transcripts from of the fall 2010 semester. One of the best ways to learn how to do reference is to observe transactions, and the chat reference transcripts provided such an opportunity. This was a great way to observe how my more experienced colleagues handled reference transactions. Since I had this goal in mind, when I was assigned the task of creating and executing an original research project for my Research Methods class, I created a project that would incorporate this goal. I began with the following questions: What kinds of questions does Albert S. Cook Library field through its Ask a Librarian service? Do the types of questions change over the course of a semester? From these initial questions, I hypothesized that the types of questions and their frequency would change over the course of the fall 2010 semester. To test this hypothesis, I would read through each IM transcript and classify the different types of questions asked. Then I would statistically analyze the data for frequency and distribution of question types across the semester. Normally, a researcher would take a random sample of

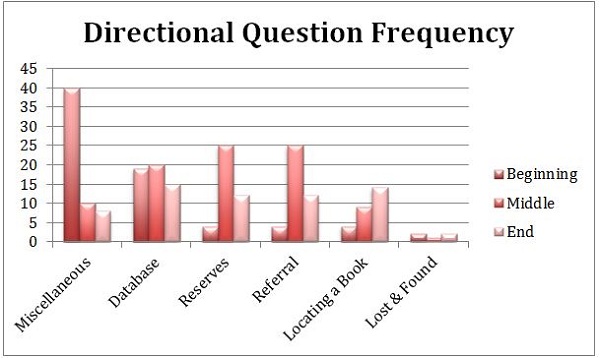

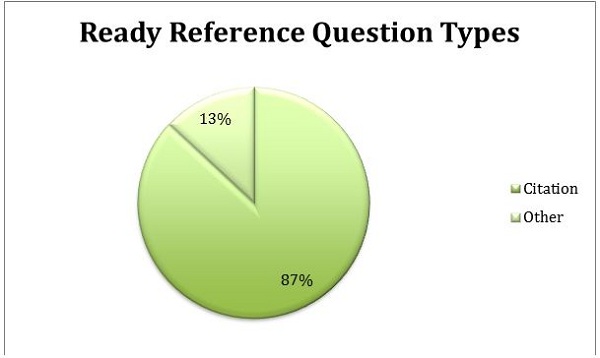

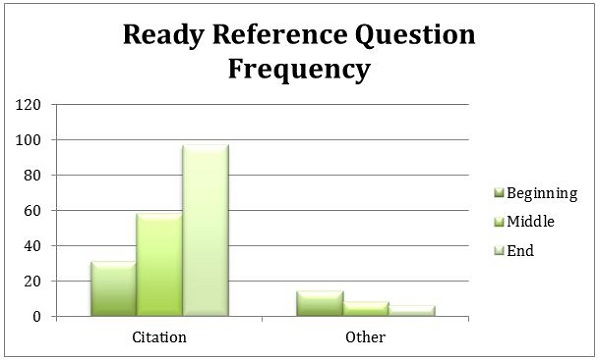

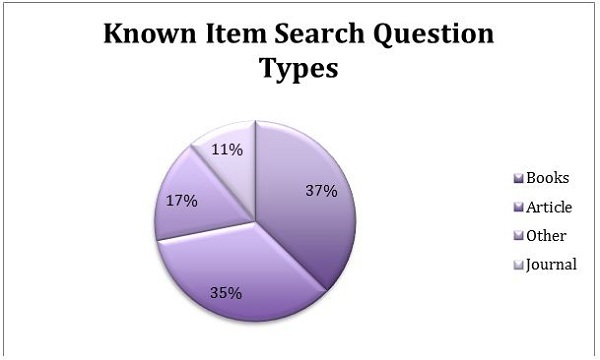

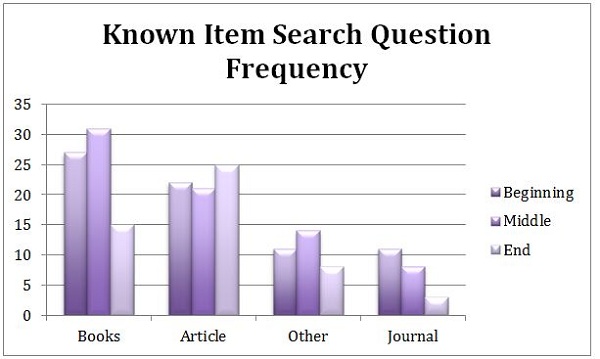

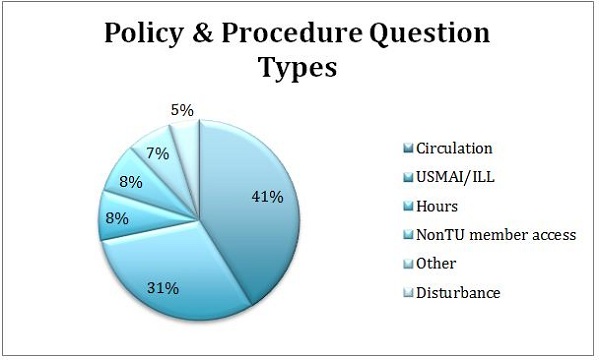

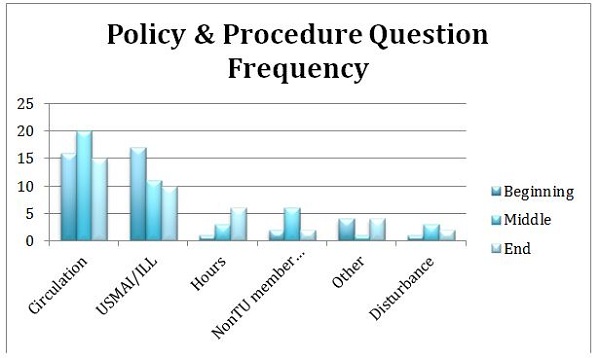

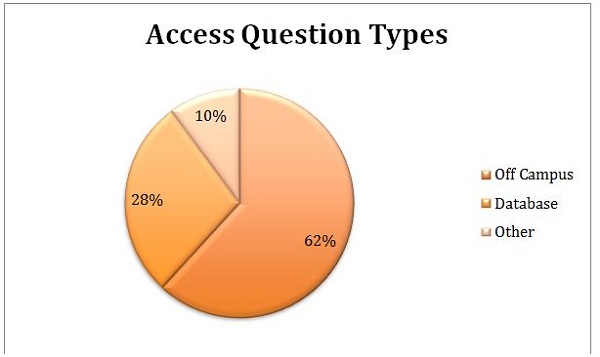

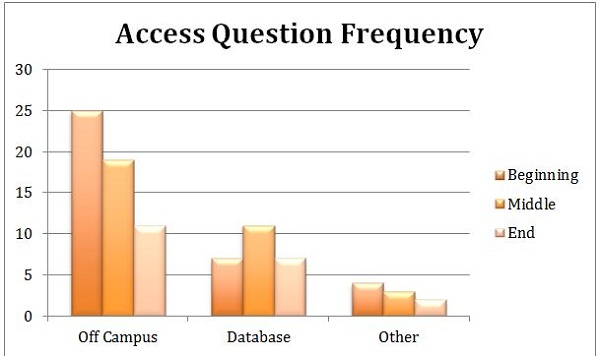

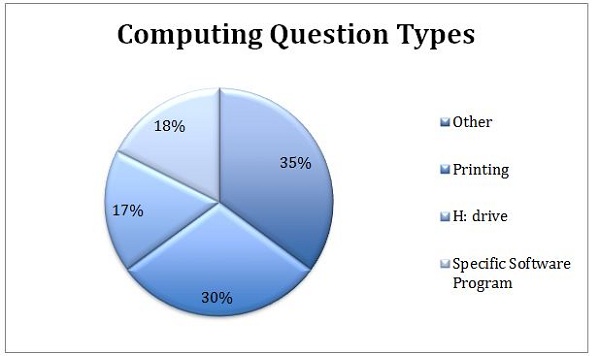

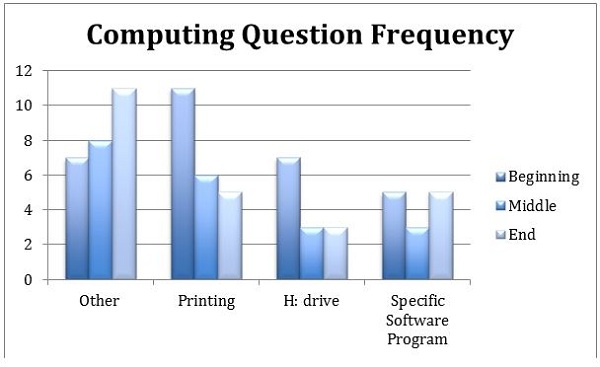

the data in order to reduce the workload. I did not take

a random sample because I had previously set the goal of

reading each transcript as a learning and training

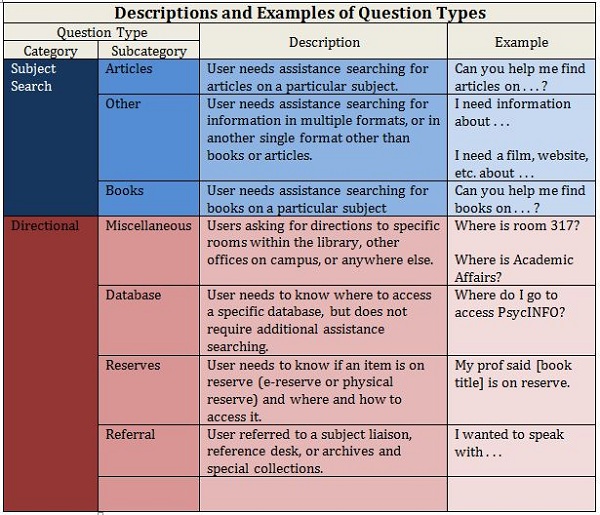

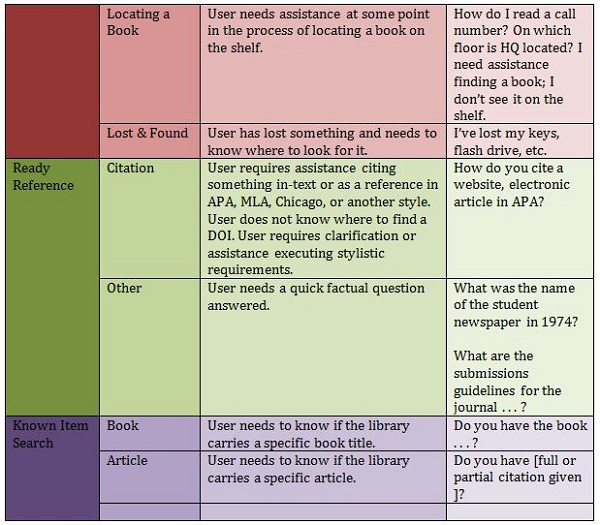

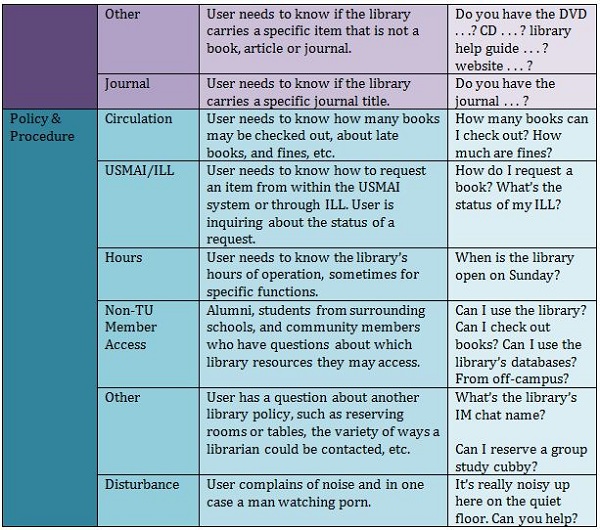

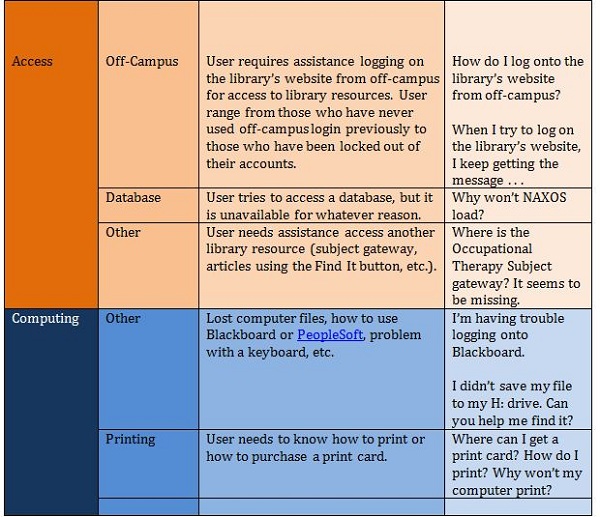

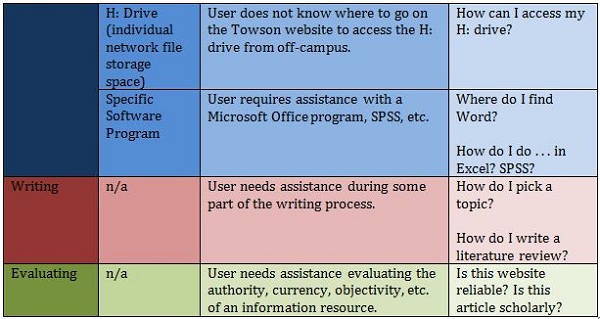

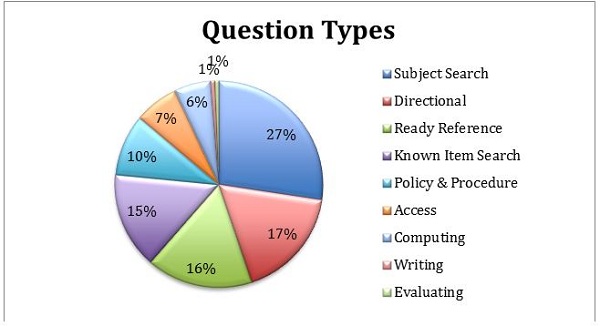

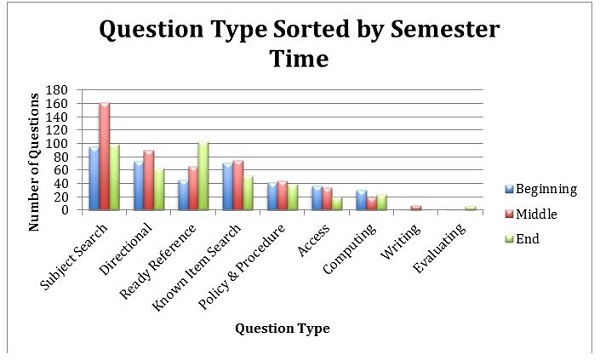

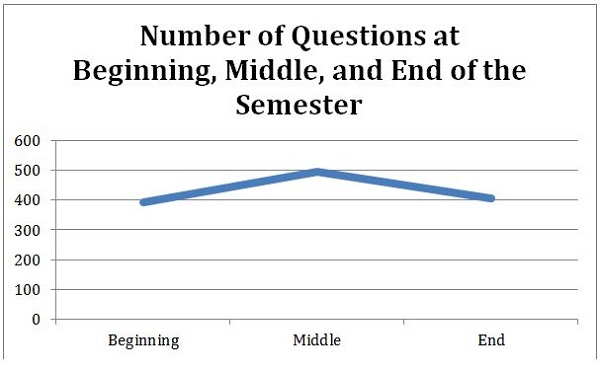

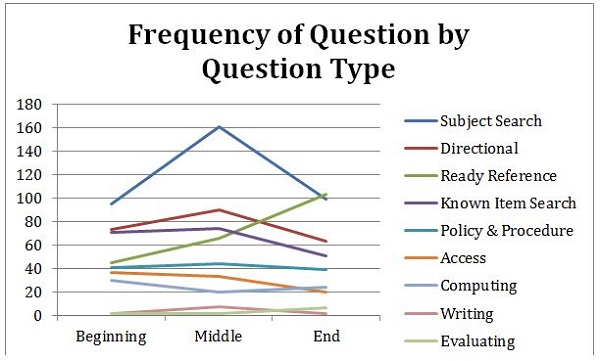

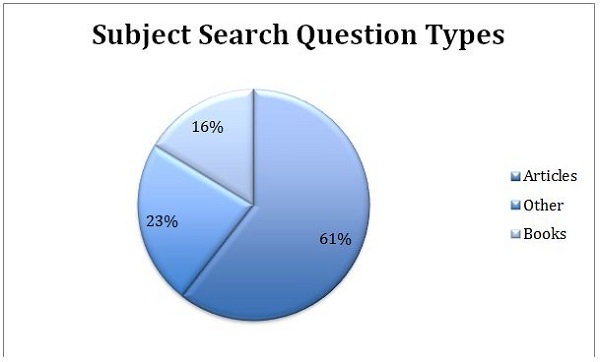

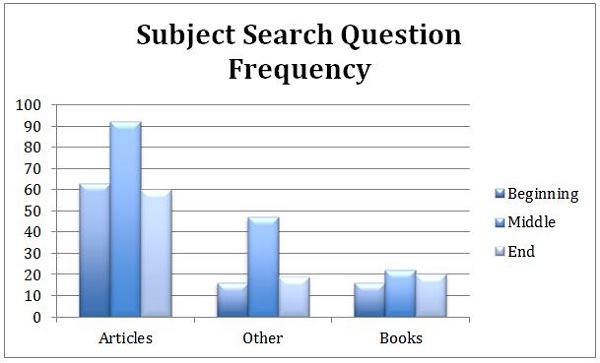

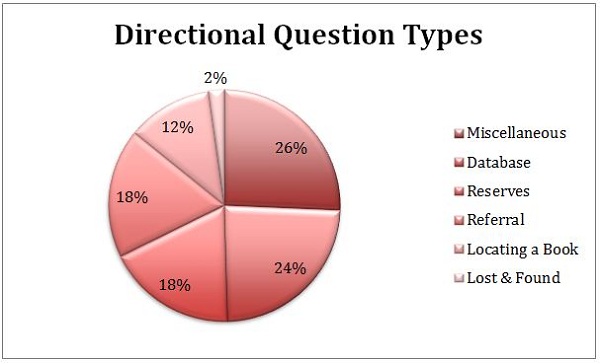

exercise. Categories for each type of question were brainstormed prior to analysis based on the researcher's knowledge of the types of questions usually asked, as well as on the categories encountered during the literature review. Despite drawing upon a large range of sources, there were still some questions the researcher was uncertain of how to categorize. For each of these questions, a short description of the transaction was noted. After all the questions were either categorized or described, the researcher created new categories as needed and reorganized the data. Question types were determined based on how the question was ultimately answered. It is a well-known fact of reference transactions that users rarely initially request what they truly need or desire. For this reason, this study analyzes question-type as interpreted by librarians, rather than users. Unanswered questions and spam were not analyzed. Unanswered questions could not be analyzed because without a reference interview, the researcher cannot be sure what the information need was. Spam was not analyzed because these questions did not represent true information needs. Nine broad categories were identified: subject search, directional, ready reference, known item search, policy & procedure, access, computing, writing, and evaluating. Seven of these categories were further subdivided. The categories of writing and evaluating were not further subdivided because there were so few questions in those categories. Figure 1 provides a detailed chart of the categories and subcategories of questions, along with descriptions and examples for each of the different question types. Questions were categorized not only by question type, but also by date. This allowed me to calculate the frequency with which certain questions were asked. Frequency of questions was calculated for three periods of the fall 2010 semester: beginning, middle, and end. The total number of days in the semester, minus days the library was closed, was divided into three equal periods of 36 days. The beginning period ran from August 25, 2010 through September 29, 2010. The middle period ran from September 30, 2010 through November 4, 2010. The end period ran from November 5, 2010 through December 15, 2010. Only one person coded the data. While this is a large job for one person, it does provide consistency in the coding of questions. Someone else may have coded the questions differently; whether a question about how to access the H: drive is computing or directional is a judgment call. There is no one right way to code reference transaction data and if the same data were presented to another researcher, it is likely s/he would code the data differently, not only assigning different questions to different codes, but also creating a different set of categories and subcategories. Results: Data & AnalysisOf the 1,564 IMs transcripts logged by LibraryH3lp, there were a total of 1,295 questions. The results show that subject searches comprised greater than one-quarter of all IM questions. Directional, ready reference, and known item searches each account for approximately one-sixth of all IM reference questions. Policy & procedure, access, computing, writing, and evaluating complete the last-quarter of IM questions. 1 in 10 questions asked over IM regarded policy & procedure. Access and computing questions comprised 7% and 6% of questions respectively. Writing and evaluating were almost non-existent with each representing only 1% of all questions asked. This data is portrayed in Figure 2. Figures 3 and 5 represent the frequency with which different questions were asked throughout different periods of the semester, and Figure 4 represents the frequency for all types of questions over the course of the entire fall 2010 semester. It is not surprising that subject searches are most frequent in the middle of the semester, while students are doing research for final papers, or that ready reference questions spike at the end of the semester when students are citing their research and have citation questions. It is also not surprising that access questions drop off towards the end of the semester when most users have already learned how to access the information they need. What is surprising is that directional questions are not heaviest at the beginning of the semester, but at the middle of the semester. This may be because students have not yet learned about this service. It makes sense that the middle of the semester is busiest overall in terms of questions asked and answered since this is when the bulk of students are completing their work. At the beginning of the semester students do not yet have their assignments, and at the end of the students are wrapping their work. Figures 6 through 19 show the distribution of different subtypes of questions within each of the major categories (subject search, directional, ready reference, known item search, policy & procedure, access, and computing). Detailed analyses of the writing and evaluating were not included due to the sparse number of questions in these areas. Figure 6 shows that questions about how to search for articles on specific subjects dominate questions about specific subjects. While Figure 7 illustrates that subject search questions are most frequent in the middle of the semester. There were quite a variety of directional questions as evidenced by figure 8. Miscellaneous directional questions topped the chart at 26% of questions. Questions about where to access specific databases, reserve items, and librarians also represent significant portions. Questions about how to locate library books on the shelves are a smaller portion of directional questions, but show that students need assistance with basic library skills. It is interesting that questions about how to locate a book are most frequent at the end of the semester (figure 9), while known item book requests are most frequent in the middle of the semester (figure 13). Reserve and referral questions are most frequent in the middle of the semester when students are involved in research and reading. Miscellaneous questions, heavily dominated by questions about how to locate different library rooms and offices on campus, are most frequent in the beginning of the semester and precipitously drop off during the middle and end of the semester when students are more oriented on campus (figure 9). Unsurprisingly, citation questions represent the bulk of ready reference questions asked via chat reference (figure 10) and these questions increase as the semester progresses (figure 11). Additionally, the few ready reference questions that are received decrease as the semester progresses (figure 11) presumably because users have gained library skills that allow them to research their own questions. Most often users will request books by title. However, users request known articles almost as frequently. Journals and other items lag behind (figure 12). Books are requested by title most frequently at the beginning of the semester, while known articles are requested most frequently at the end of the semester (figure 13). When it comes to policy & procedure, questions about circulation predominate, but are followed closely by questions about USMAI and ILL, book loans from other institutions within in University of Maryland system as well as interlibrary loan (figure 14). Questions about hours are most frequent at the end of the semester when students may need greater access to library resources as they finish end-of-semester projects and as the library's hours lengthen to accommodate the needs of students. Questions about non-TU member access increases in the middle of semester. Without a breakdown of who is asking about access (alumni, students from other schools, community members), it is difficult to determine why those questions are most frequent in the middle of the semester. USMAI and ILL predominate at the beginning of the semester, most likely because users are unfamiliar with the process at the beginning of the semester. For access questions, users most frequently ask about how to access the library's resources from off-campus (figure 16). However, figure 17 shows that these questions steadily fall off during the semester as students gain knowledge of and comfort with library resources. Questions about problems accessing databases are most frequent during the middle of the semester (figure 17) when students are busiest asking questions about where to access databases (figure 9) as well as how to search for articles on a specific subject (figure 7). This further reflects the reality that the middle of the semester is the heaviest time for research. While computing questions are one of the least frequently asked question types (figure 2), this question type consists of the greatest variety of questions, and is why the subcategory other is the largest subcategory within the computing questions category (figure 18). Printing questions are the next-most frequent type (figure 18), but this question type drops off as the semester progresses and students learn the ins and outs of the printing system (figure 19). H: drive questions, like printing questions, quickly drop off as students learn the ropes (figure 19). Specific software questions are most frequent at the beginning of the semester, when students are becoming acquainted with the software available to them, and at the end of the semester, when students are pushing the limits of their knowledge as they compose their final projects (figure 19). Discussion & Suggestions for Future ResearchBy and large, the results confirm anecdotal evidence

and librarian perceptions. Librarians have noted that

citation questions increase markedly at the end of the

semester when students are finishing up their papers and

that more students need to know how to print, find their

H: drive, and access the library's resources from

off-campus at the beginning of the semester. It is also

not surprising that the greatest need of students

overall is searching for information, very often

articles, about specific subjects as a great deal of

library instruction time is expended upon this subject.

Information can be difficult to find if you do not

understand subject headings, Boolean logic, or how to

choose the best database for your topic. What some may

find surprising is that students ask these questions,

which may require rather lengthy answers, via IM, which

has been perceived as a medium for quick questions and

which often lacks the benefit of visuals. Librarians could use this evidence to post help guides directly to the library's homepage where students will see them immediately. Help guides for off-campus access could be posted at the beginning of the semester when this question-type predominates; citation help guides could be posted at the end of the semester, and searching guides could be posted in the middle of semester. The library already devotes a portion of its homepage to spotlight services and events. One spotlight in particular directs students to help guides, but it could provide links to specific help guides depending upon the needs of the students based upon the time in the semester. The number of circulation and USMAI and ILL questions, as well as the expertise required to answer those questions, suggests that having circulation and ILL staff answering IMs may be beneficial to our students. It is easy enough for a user to make a phone call, but if the user has contacted the library via the chat reference service, it is safe to say s/he would prefer to interact with staff using that conduit. If a similar study were undertaken in the future, creating categories for referral to professor, spam, and unanswered questions may be worthwhile. It is not uncommon for students to ask questions of librarians that are best clarified by their professors, such as questions about the parameters and expectations of specific assignments or recommendations of specialists within a field of study. Librarians refer students who ask these types of questions to their professors. If spam and unanswered questions had been recorded, the data could have provided a more complete picture of the quantity of questions being asked and answered. These categories do not represent a majority, but it would be best to track them. There are many additional areas of chat reference to explore. One such opportunity would be to analyze chat transcripts for accuracy. Samples could be taken from the different time periods in the semester to see if and how performance of reference changes. Samples could also be taken from certain question types to determine a best practice for different question types. While librarians should strive to answer all questions as fully and accurately as possible, it may be helpful to hone in on specific types of questions that are frequent or troublesome to determine the best way to approach them. A similar study could be conducted to analyze whether there is any difference in the quality of reference transactions between those questions answered at the reference desk and those questions answered off-desk. A comparison of the types of questions that are received from different access points, including face-to-face, phone, texting, and chat, might establish patterns in reference use, giving librarians a greater understanding of user habits, and consequently staffing needs. It would be interesting to see if certain access points were used more frequently for certain types of questions. A discussion could then begin as to why certain channels to the library received more or less use. This data would be greatly supplemented with

information about user and librarian perceptions of the

Ask a Librarian service. This information could be

gleaned using a survey or more deeply investigated in

focus groups. To establish usage patterns, it would be

good know where students access the Ask a Librarian

service (are most users on or off campus?), how often

users frequent the service, and the level of student

satisfaction with the service. These are but a few areas of exploration for future IM

reference research. Surely, more areas will evolve as IM

reference and other mobile reference and library

services evolve. ConclusionThis analysis of chat reference questions, while confirming anecdotal evidence, provides a more complete understanding of types of questions asked of librarians via chat reference, as well as frequency of different types of questions. This information assists librarians in understanding and anticipating user needs, and allows them to develop additional tools, resources, and skills for assisting library users. While a worthwhile endeavor, it would be best supplemented with additional facets of assessment to establish a more well-rounded portrait of chat reference services and their use at Towson University. As a library student, this research project provided me with an opportunity to understand patterns of usage for chat reference across a semester. Without undertaking this project, these patterns may not have become apparent to me until I had experienced several semesters of reference service in an academic setting. Furthermore, I was afforded the opportunity to build my anecdotal knowledge of both the types of questions that users ask, as well as the ways librarians answer questions, which has surely augmented my ability to interview users and answer their questions. ReferencesArnold, J. and Kaske, N. K. (2005). Evaluating the quality of a chat service. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 5(2), 177-193. DOI: 10.1353/pla.2005.0017 Breitbach, W., Mallard, M., and Sage, R. (2009). Using meebo's embedded Im for academic reference services: A case study. Reference Services and Sources, 37(1), 83-98. DOI: 10.1108/00907320910935011 Broughton, K. M. (2003). Usage and user analysis of a real-time digital reference service. The Reference Librarian, 38(79/80), 183-200. DOI: 10.1300/J120v38n79_12 Foley, M. (2002). Instant messaging reference in an academic library: A case study. College & Research Libraries Quarterly, 63(1), 36-45. Retrieved from http://crl.acrl.org/content/63/1/36.full.pdf Kibbee, J., Ward, D., and Ma, W. (2002). Virtual service, real data: Results of a pilot study. Reference Services Review, 30(1), 25-36. DOI: 10.1108/00907320210416519 Lupien, P. and Rourke, L. E. (2007). Out of the question!... How we are using our students' virtual reference questions to add a personal touch to a virtual world. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 2(2), 67-80. Retrieved from http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/EBLIP Maximiek, S., Rushton, E., and Brown E. (2010). Coding into the great unknown: Analyzing instant messaging session transcripts to identify user behaviors and measure quality of service. College & Research Libraries, 71(4), 361-374. Retrieved from http://crl.acrl.org/content/71/4/361.short Passonneau, S. and Coffey, D. (2011). The role of synchronous virtual reference in teaching and learning: A grounded theory analysis of instant messaging transcripts. College & Research Libraries, 72(3), 276-295. Retrieved from http://crl.acrl.org/content/72/3/276.full.pdf+html Rourke, L. and Lupien, P. (2010). Learning from chatting: How our virtual reference questions are giving us answers. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 5(2), 63-74. Retrieved from http://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/ index.php/EBLIP Sears, J. (2001). Chat reference service: An analysis of one semester's data. Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, 32. Retrieved from http://www.library.ucsb.edu/istl/01-fall/article2.html Towson University. (2011, January). About TU: Towson at a Glance. Retrieved from http://www.towson.edu/main/abouttu/glance/index.asp Towson University, Albert S. Cook Library. (2010). Albert S. Cook Library at Towson University: Inspiring a Journey of Learning[Brochure]. Towson, MD. Retrieved from http://cooklibrary.towson.edu/docsLibrary/publicity/libraryBrochure_1-13-10.pdf Towson University, Albert S. Cook

Library. (2011, April 15). Mission &

Vision. Retrieved from http://cooklibrary.towson.edu/missionStatement.cfm Towson University, Office of

Institutional Research. (2011, October 7). Fact Sheet Fall 2011.

Wan, G., Clark, D., Fullerton, J., Macmillan, G., Reddy, D. E., Stephens, J., and Xiao, D. (2009). Key issues surrounding virtual chat reference model: A case study. Reference Services Review, 37(1), 73-82. DOI: 10.1108/00907320910937299 Author's BioAmanda Youngbar is Library Associate for Learning Commons at Towson University's Albert S. Cook Library and is in pursuit of her MLIS in University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee's School of Information Studies’ distance learning program. She has a bachelor’s in women, gender & sexuality studies and a master’s in liberal studies. |

Contents |

Copyright, 2013 Library Student Journal | Contact

international · peer reviewed · open access

international · peer reviewed · open access